At the ripe young age of 98, Nanammal from India continues to inspire generations of youth with yoga. Ida Keeling from Brooklyn set the world record in the 100m (category of 80 and older), when she finished the race in less than 90 seconds at the age of 100.

Finally there’s Charles Eugster, a bodybuilder and sprinter with multiple world records for his age group under his belt. He’s considered to be the world’s fittest 96 year-old. These exceptionally healthy and fit seniors prove to us that staying active is the key to a long and healthy life.

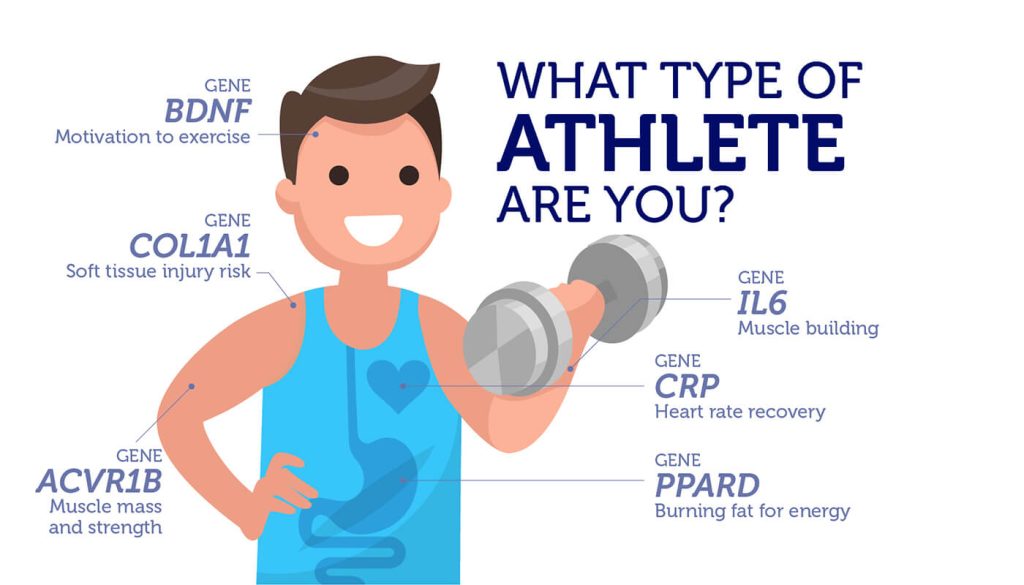

But that doesn’t mean that all of us will equally benefit from exercise. Undeniably, some of us respond better to exercise than others, particularly when it comes to losing weight and keeping it off. Did you know these individual differences in metabolism are sometimes rooted in our DNA?

Take the PPARD gene for example. A single change in PPARD can increase the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, but exercise is all that is needed to minimize this risk.

To burn sugar or fat?

Our talent for losing weight and keeping it off depends wholly on how efficient we are at breaking down fat. Burning fat has a number of advantages during exercise. It generates twice as much energy as sugar, and preserves our sugar reserves for organs like the brain that can’t burn fat.

But, our bodies prefer sugar as sources of energy rather than fats. So, we need to train our bodies to burn fats. This is exactly what exercise does – especially activities that last at least 30 minutes.

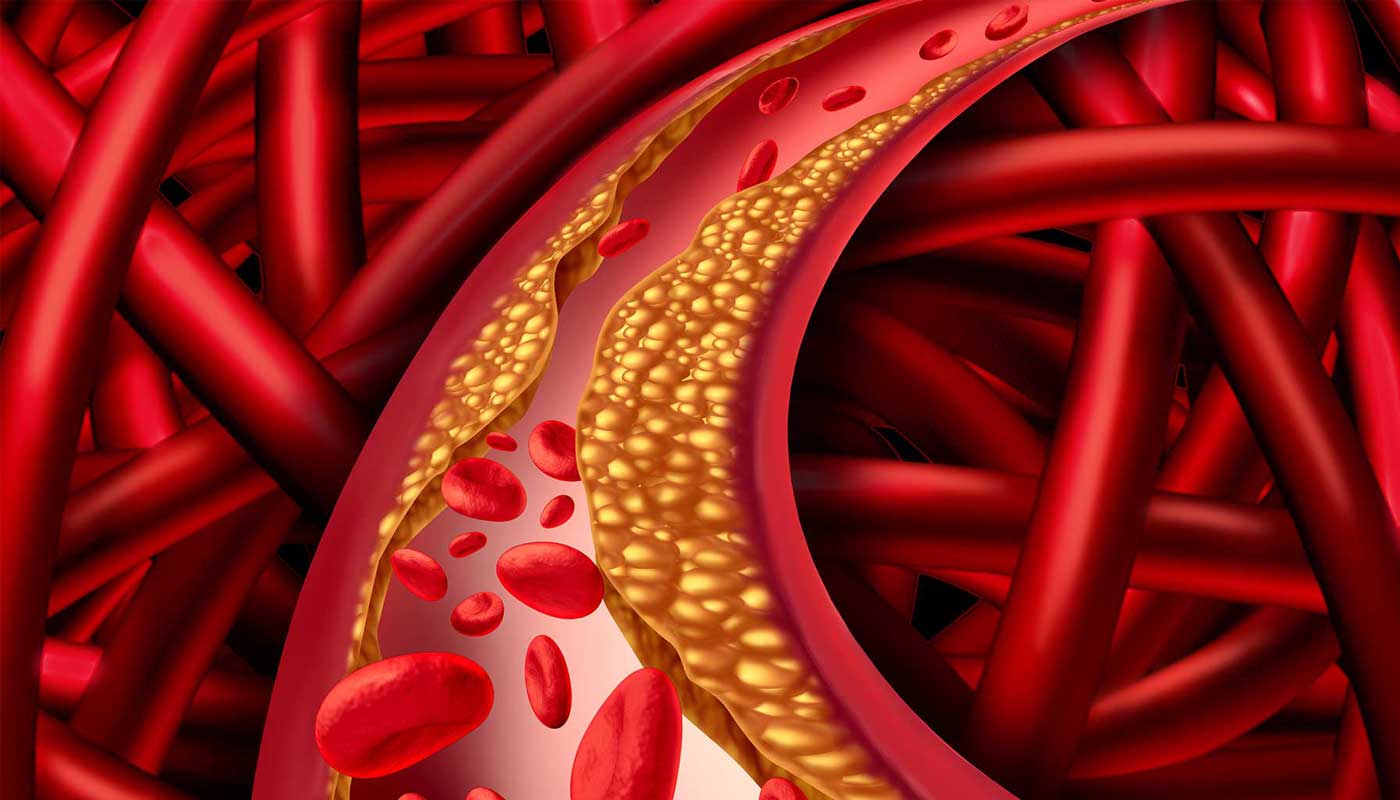

Endurance activities encourage our muscles to adapt, and they switch from burning sugars to burning fats. Not only that, regular exercise increases the levels of “good” high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), which protects us against cardiovascular disease.

The PPARD gene

The PPARδ protein (encoded by the PPARD gene) is key to this energy choice between sugars and fats. What’s more, it also governs the exercise-mediated changes in HDL-C.

PPARδ controls the activity of many other genes, particularly the ones involved in fat breakdown. Endurance exercises increase PPARδ levels, enhancing our ability to use fats for energy.

Studies in mice show that artificially elevating PPARδ levels make them resistant to weight gain, even when they didn’t exercise. This means that differences in PPARδ levels can at least partly explain the why some people can lose more weight by exercising compared to others.

The PPARD variant

Those of us who inherit a version of PPARD, called rs2016520, have lower levels of HDL-C, and higher levels of “bad” low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), enhancing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

But all is not lost. According to one study, Caucasian men with rs2016520 experienced significantly higher increases in HDL-C levels following endurance training compared to those with the normal version of PPARD.

This means people who are at risk, benefit more from the “HDL-raising effect” of exercise, and exercise can mitigate their predisposition to diseases like type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Your risk of heart disease

Yet, the story of PPARD is far from simple. The link between PPARD, HDL-C and exercise appears to be ethnicity dependent. Also, the rs2016520 version linked to high risk of cardiovascular disease in sedentary people, is actually highly prevalent among elite endurance athletes.

So there seems to be a disconnect between extreme athletic potential in highly active individuals, versus how an average person with the same variant will reap health benefits from exercise. With so many studies looking at how genetic changes impact our response to exercise, future studies will no doubt settle this intriguing conundrum.

Will your body benefit from exercise, to increase your “good” cholesterol levels? Find out with the DNA Fitness Test.