The banner outside the gymnasium reads, “It’s in you to give.” After waiting in line for over two hours, Emily is happy that it’s finally her turn. A few routine questions later, it’s time for the finger stick test.

The nurse pricks her finger, uses a small glass tube to collect the blood and releases a single droplet into a container filled with a clear blue liquid. But, as the timer goes off, the only thing that is sinking is Emily’s heart. Her hemoglobin levels just aren’t measuring up.

Hemoglobin tests

Testing for hemoglobin levels is standard practice at every blood clinic. Not only does it ensure the quality of blood, it also accounts for the health of the donor.

Low hemoglobin levels are an indication that you might be anemic, and that you aren’t getting enough iron. However, if you are positive that you eat enough red meat, there may be another reason for why you failed the hemoglobin test.

The reason is genetics. Genes control the fate of every nutrient that enters the body, from how much is absorbed, to whether it is stored or broken down. Two genes in particular, TF and TMPRSS6, affect iron levels in the blood.

The role of iron

Iron is a mineral with several essential functions in the body. It constitutes the core of both hemoglobin, the molecule that carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body, and myoglobin, a protein that provides oxygen to the muscles.

Oxygen is bound to iron inside these proteins, as it is delivered from the source to its destination. Iron is also essential for growth, for normal cell function, and for the production of connective tissue and some hormones.

Iron obtained from food can be of two forms: heme and non-heme. Plant sources and fortified foods like cereals only contain the non-heme form, whereas animal sources contain both types. For natural sources of iron and recommended dietary allowances refer to the tables at the end of this article.

Iron metabolism

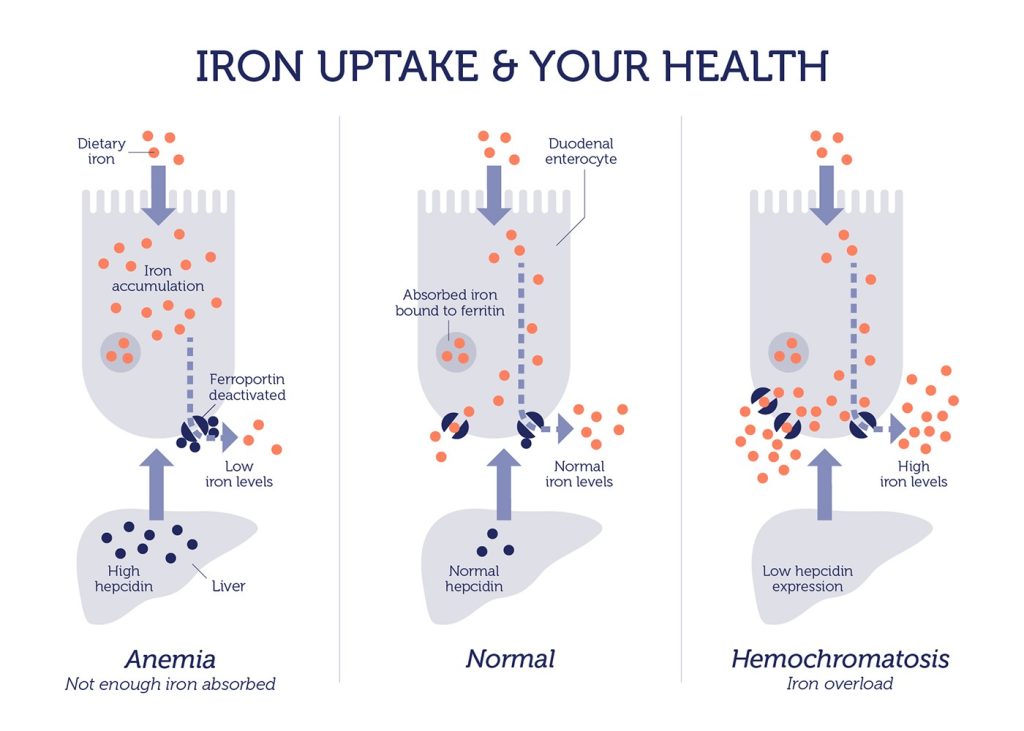

Iron metabolism requires the cooperation of many genes. Genetic variants of two of these, TF and TMPRSS6, are linked to lower iron levels in the blood. Genetic variants are small changes in DNA that can result in different versions of a protein.

The TF gene encodes an iron-binding protein called transferrin. It controls how much free iron is found in the blood.

People who inherit the TF variant, known as rs3811647 A, make more transferrin. However, this altered protein binds less iron, so less iron is transported around the body.

Variants of the TMPRSS6 gene (which encodes matriptase-2) affect the control of a second protein called hepcidin. Hepcidin decreases both the absorption of iron in the intestine and the release of iron from blood and liver stores, resulting in lower blood iron levels.

People with TMPRSS6 variants make less matriptase-2. This means hepcidin levels remain abnormally high, preventing the absorption of more iron from the diet.

Iron-deficiency anemia

Low iron levels inhibit the production of hemoglobin, resulting in a reduced red blood cell count. When the body can’t supply enough red blood cells to meet its demands, it manifests as anemia. Anemia affects over 1.6 billion people around the globe.

Symptoms include tiredness, fatigue, pale skin, shortness of breath, headaches, dizziness, and unusual cravings for non-nutritive substances like ice or dirt. These initial symptoms of deficiency can go unnoticed. But if left untreated, anemia can have serious repercussions. These include impaired cognitive function, disturbances in the digestive system, and impaired immunity.

Pregnant women, young children and frequent blood donors are at a much higher risk of iron deficiency. Using supplements to mitigate the risk requires caution (see end of this article for tolerable upper limits for iron).

Excess iron and the risk of hemochromatosis

On the flip side, too much iron can upset your digestive system, leading to constipation, nausea, vomiting, faintness and abdominal pain. Iron poisoning due to high doses can be deadly in children, and cases of extreme overdose can lead to organ failure, coma and death in an adult.

Hereditary hemochromatosis is a distinct genetic condition that leads to excessive iron accumulation and it affects 1 out of 200 individuals in the U.S. More information on hereditary hemochromatosis can be found here.

What about your iron levels?

Iron is one of those nutrients that is essential. Yet, at the same time has toxic side effects when in excess. Consequently, both deficiency and overload of iron are detrimental to our health.

Take the DNA Nutrition Test today to find out whether you need to tweak your iron intake. You can use this information to personalize your diet, so you can maintain your iron intake at a healthy level.

Recommended dietary allowances for iron

Recommended dietary allowances are shown in milligrams (mg). Adequate intake for infants from birth to 12 months is equivalent to the mean intake in healthy, breastfed infants.

| Age | Male | Female | Pregnancy | Lactation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 months | 0.27 mg | 0.27 mg | ||

| 7–12 months | 11 mg | 11 mg | ||

| 1–3 years | 7 mg | 7 mg | ||

| 4–8 years | 10 mg | 10 mg | ||

| 9–13 years | 8 mg | 8 mg | ||

| 14–18 years | 11 mg | 15 mg | 27 mg | 10 mg |

| 19–50 years | 8 mg | 18 mg | 27 mg | 9 mg |

| 51+ years | 8 mg | 8 mg |

Selected foods sources of iron

The Daily Value (DV) for iron is 18 mg for adults and children age 4 and older. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) developed DV, so you can compare the nutrient contents of products within the context of a total diet.

| Food | mg per serving | Percent DV |

|---|---|---|

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 100% of the DV for iron, 1 serving | 18 | 100 |

| Oysters, eastern, cooked with moist heat, 3 ounces | 8 | 44 |

| White beans, canned, 1 cup | 8 | 44 |

| Chocolate, dark, 45%–69% cacao solids, 3 ounces | 7 | 39 |

| Beef liver, pan fried, 3 ounces | 5 | 28 |

| Lentils, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Spinach, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Tofu, firm, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Kidney beans, canned, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Sardines, Atlantic, canned in oil, drained solids with bone, 3 ounces | 2 | 11 |

| Chickpeas, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Tomatoes, canned, stewed, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Beef, braised bottom round, trimmed to 1/8” fat, 3 ounces | 2 | 11 |

| Potato, baked, flesh and skin, 1 medium potato | 2 | 11 |

| Cashew nuts, oil roasted, 1 ounce (18 nuts) | 2 | 11 |

| Green peas, boiled, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Chicken, roasted, meat and skin, 3 ounces | 1 | 6 |

| Rice, white, long grain, enriched, parboiled, drained, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Bread, whole wheat, 1 slice | 1 | 6 |

| Bread, white, 1 slice | 1 | 6 |

| Raisins, seedless, ¼ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Spaghetti, whole wheat, cooked, 1 cup | 1 | 6 |

| Tuna, light, canned in water, 3 ounces | 1 | 6 |

| Turkey, roasted, breast meat and skin, 3 ounces | 1 | 6 |

| Nuts, pistachio, dry roasted, 1 ounce (49 nuts) | 1 | 6 |

| Broccoli, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Egg, hard boiled, 1 large | 1 | 6 |

| Rice, brown, long or medium grain, cooked, 1 cup | 1 | 6 |

Tolerable upper intake levels for iron

These upper limits apply to both food and supplement sources of iron. These upper limits do not apply to individuals taking high doses of iron under medical supervision.

| Age | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| 0–12 months | 40 mg | 40 mg |

| 1–13 years | 40 mg | 40 mg |

| 14–18 years | 45 mg | 45 mg |

| 19+ years | 45 mg | 45 mg |

Recommended dietary allowances, food sources and tolerable upper limits are obtained from the Iron Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet (National Institutes of Health).