It’s a warm day in the middle of July. Two young women are sitting at the waiting area of a prestigious law office in New York, and hoping to be their newest recruit.

Amanda is the first candidate. In her blue suit that matches her keen eyes, she appears calm and collected. Her rival Christine was at the top of her class. Her quick wit and perseverance makes her a formidable opponent.

If they perform equally well in their interviews, can you predict which one of them will go home the winner? Would it help if you knew that Christine’s face looked red, blotchy and swollen since her eczema had flared-up?

None of us want to admit it, but everything else being equal, we all know that Amanda was probably the first pick. That’s the power of a first impression – easily set, impossible to change. Many people with a visible skin condition have to face this sad reality everyday.

Dry, irritated skin

Eczema is a skin condition characterized by inflamed or irritated skin. Approximately 30 million adults in the US are affected by it.

The risk of developing red, itchy skin is largely inherited. Variation in one protein found in our skin, filaggrin, is strongly linked to eczema. DNA changes in the FLG gene (encodes filaggrin) contribute to our genetic predisposition to eczema.

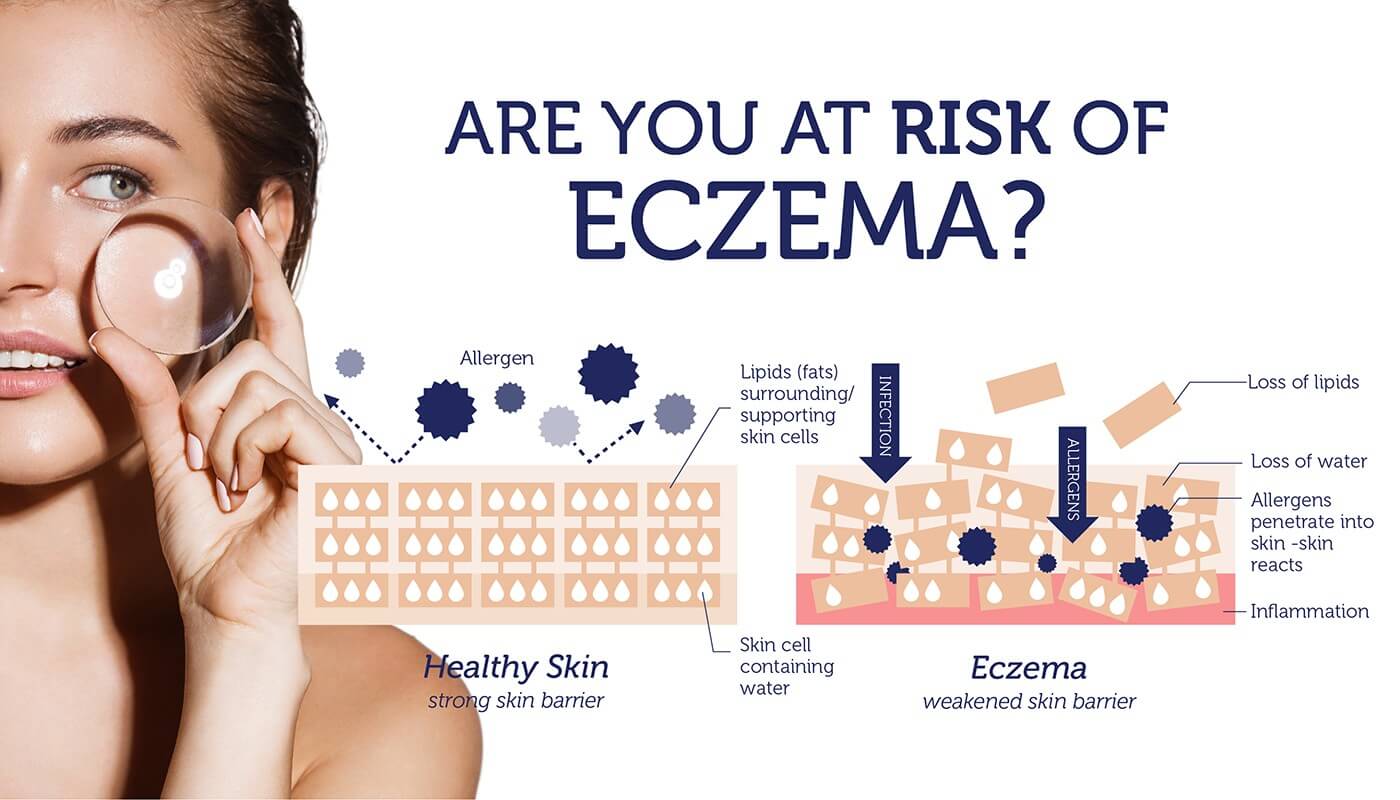

Skin as a barrier

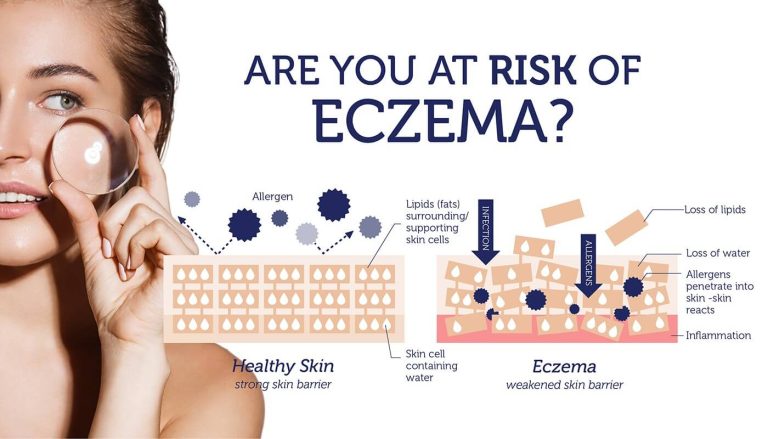

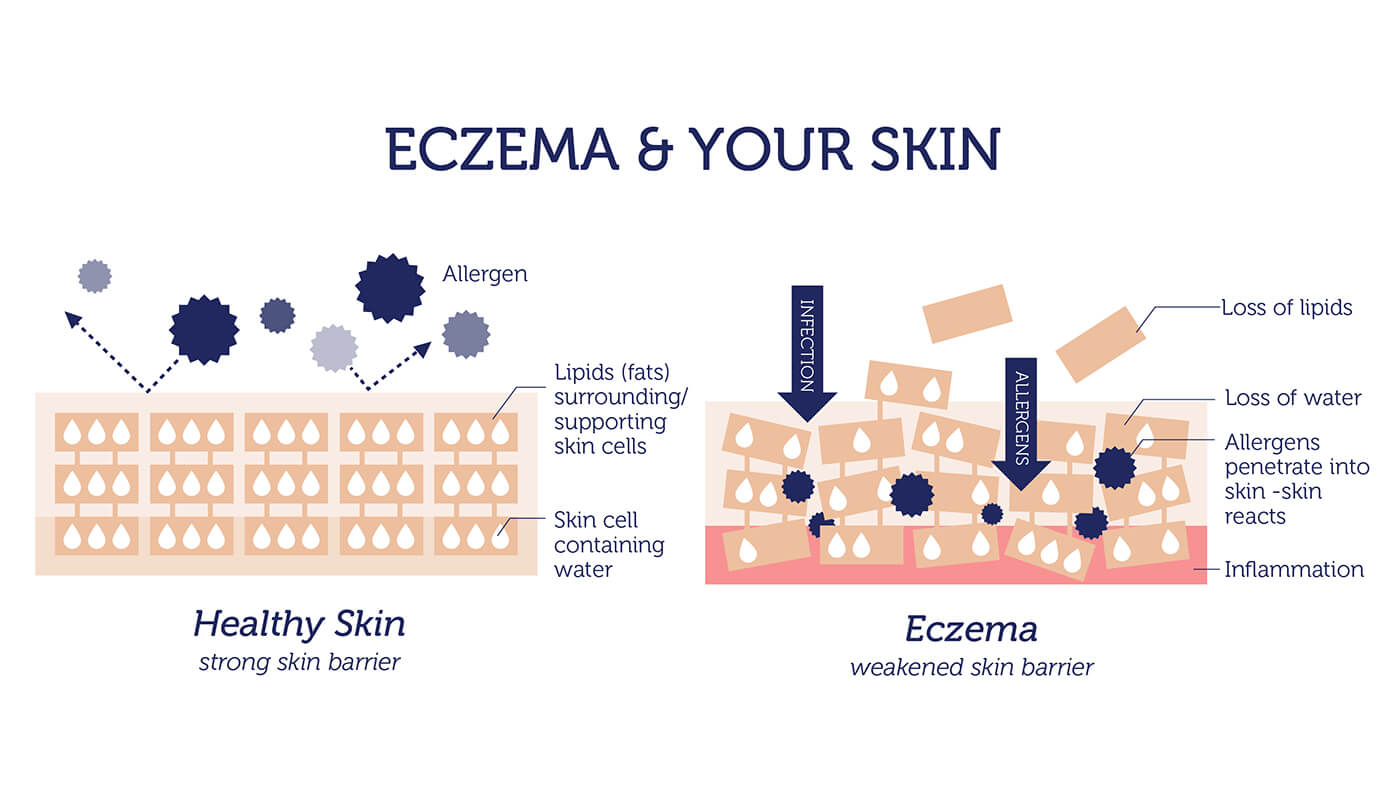

We often think of our skin in relation to beauty. We forget that it also serves as a barrier against the environment, keeping out pollutants, irritants and allergens.

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of our skin. It consists of 15 to 20 layers of flattened, dead cells. Two proteins, keratin and filaggrin, are responsible for establishing and maintaining the structure of this impenetrable layer of skin.

The function of filaggrin

Filaggrin assembles keratin filaments together, causing them to collapse down into several layers of skin. Transglutaminases will then glue these layers together. Then the body will break down filaggrin, and use it to give our skin moisture.

Filaggrin is therefore key to forming the protective and properly moisturized barrier of our skin. The barrier layer loses its structure without filaggrin, so allergens easily penetrate the skin, initiating an immune response.

Eczema is exactly that – an immune response to environmental triggers. This is why structural changes to the barrier layer and genetic defects in the FLG gene contribute to the risk of eczema.

FLG variants and the risk of eczema

There are over 40 distinct genetic changes in the FLG gene. Each of these changes either reduce or completely abolish the production of filaggrin. Some of these variants are linked to eczema (also known as atopic dermatitis).

Interestingly, FLG mutations appear to be distinct between different populations. For example, people with Japanese ancestry exclusively inherit two variants of FLG called S2889X and S3296S, while Europeans carry two other variants, rs558269137 and rs61816761.

In one study, people with FLG variants were at a much high risk for developing atopic dermatitis. Another study highlighted the fact that 27% of the patients with atopic eczema had one or more changes in the FLG gene.

To date, FLG remains one of the genes with the strongest evidence for genetic predisposition to eczema.

Taking control of your eczema

Eczema is a common skin disorder that affects many children. Sometimes the problems continue into adulthood. The severity of symptoms, as well as the triggers of eczema vary from person to person.

FLG variants are included in the DNA Skin Health Test. Knowing ones risk for developing eczema, especially in the case of an infant, is most definitely the best way to keep this skin condition under control.