When biologists talk about monogamy, they mean genetic or sexual monogamy. A scenario where two partners in a relationship are sexually exclusive.

But, according to recent studies “social monogamy” may be on the rise, leaving researchers to struggle with the question of whether this is a new social norm, or whether it actually reflects certain aspects of human nature.

Social monogamy

Social monogamy refers to a couple that share living arrangements and cooperate in a family structure, but are not sexually exclusive.

Scientifically, monogamy is less advantageous to a man than it is for a woman. A man who mates with multiple women will have more children, and therefore spread his genetic material more widely. But, this benefit is balanced against the evolutionary advantage gained from the human family structure.

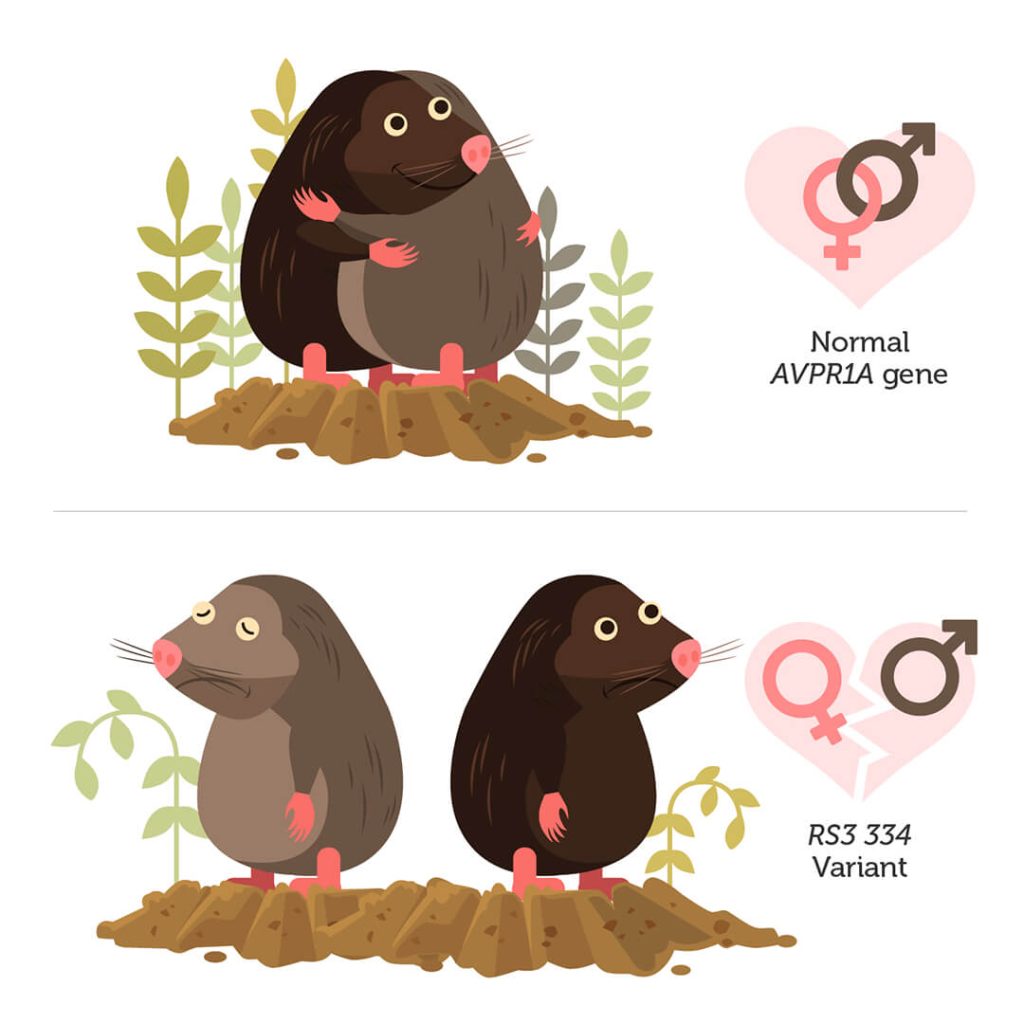

Could DNA changes in a single gene, AVPR1A dictate the fate of a family?

Vasopressin and behavior

Vasopressin and the vasopressin receptor (encoded by AVPR1A) are best known for their roles in water retention and blood pressure. However, both vassopressin (when directly released into the brain) and specific DNA changes in the AVPR1A gene can also influence social behavior.

For example, dancers have DNA changes in AVPR1A that appear to be important for developing social interactions on the dance floor. Musical ability is associated with other AVPR1A changes, since the pathways in the brain that we use to perceive music are the same ones we use when we connect with other people.

One such genetic change is responsible for turning AVPR1A into the “male pair-bonding” gene.

Male pair-bonding gene

The specific AVPR1A variant linked to decreased pair-bonding in men is known as the RS3 334 allele. Men with the RS3 334 allele are less likely to form strong bonds with their partners.

In one study, 34% of men with this version of the gene experienced marital crisis or the threat of divorce, compared to 15% of men who do not have the RS3 334 allele. Men with the “pair-bonding” allele were also more likely to chose cohabitation over marriage. They also tend to be less affectionate towards their partner.

A fear of commitment?

So, if some men are genetically pre-programmed to have decreased pair-bonding, can their behavior really be described as a “fear of commitment”? This actually is a small part of a much larger question; just how much are we defined by our genes?

We will soon be entering a future where our genetic makeup will be readily available. Whether we use this knowledge to excuse our bad behaviors, to choose to seek education and counselling, or to make a personal commitment to overcome our limitations, will ultimately determine how this genomic revolution will impact our society.

Will your pair-bonding gene affect the fate of your family. Find out with the Male Pair-Bonding Gene AVPR1A Test.