Jörg Jenatsch was a man devoted to his country, so much so that he converted from Protestantism to Catholicism in a bid to bring Valtellina back under the control of Graubünden. But, war crimes eventually caught up with Jenatsch, and he was assassinated by a group of masked murderers. Long after his death and hasty burial, his gravestone was moved and his remains were lost. This is the story of rediscovering the grave of Jenatsch. And how DNA analyses confirmed the authenticity of his remains.

A minister turned political leader

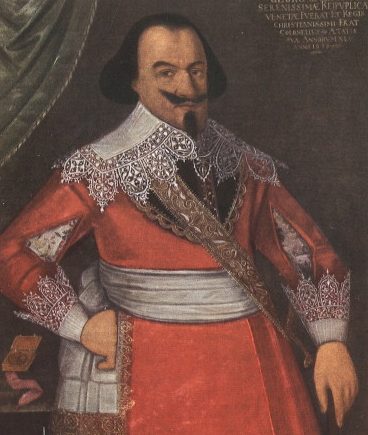

Jörg Jenatsch was a Protestant minister and political leader in Graubünden (now part of present-day Switzerland) at the time of the Thirty Years’ War.

This war lasted from 1618 to 1648, and was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts of human history.

Jenatsch played a key role during the war. He helped protect the independence of Valtellina, an important north-south thoroughfare within Graubünden.

Despite being a man of the cloth, Jenatsch was also involved in many murders and assassinations, as one of the board of Protestant ‘clerical overseers.’

The most notorious was perhaps the murder of Pompeius von Planta, the leader of the rival party. A group led by Jenatsch killed Pompeius in front of his daughter and left him pinned to the floor with an axe. Soon after, Janatsch and many other Protestants were forced to flee the country.

During his exile he lost his position as a pastor. From then on Jenatsch acted solely as a military entrepreneur, rising rapidly through the ranks to become colonel of his own regiment. In 1631, he was recruited by the French to drive the Spaniards out of Valtellina.

However, after a successful campaign, Jenatsch (and many other military leaders) quickly realized that the French were just as unwilling as the Spaniards to restore Valtellina back to the control of Graubünden.

Murdered during Carnival

In 1635, Jenatsch converted to Roman Catholicism and became a leader of a secret alliance, the Kettenbund, who negotiated secretly with the Spaniards and Austrians (his previous enemies).

The Kettenbund launched a strike that drove the French (his old allies) out of Graubünden. Jenatsch then spent two years trying to negotiate with Spain and Austria for the return of Valtellina to Graubünden rule.

He also unsuccessfully tried to convince Ferdinand II (Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire) to grant him a title of nobility.

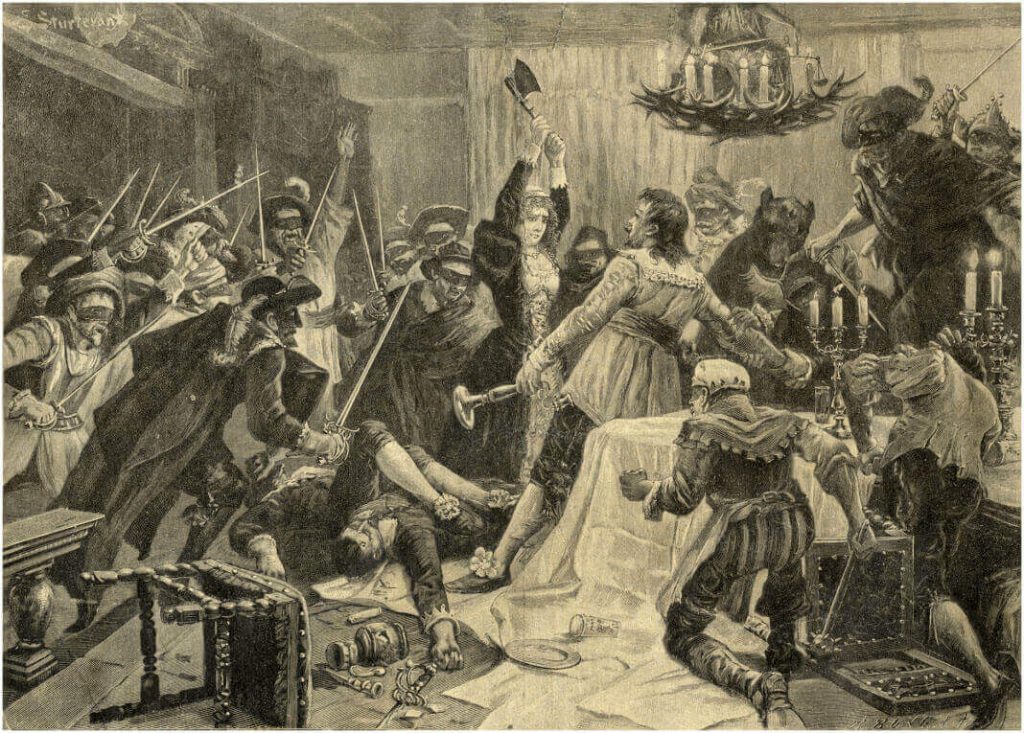

But alas, before either goal was achieved Jenatsch was assassinated. The masked murderers, led by a man dressed as bear, killed Jenatsch with an axe during the festive celebration known as Carnival.

The murderer was never found. However, many suspect it was Rudolph von Planta (Pompeius’ son) seeking blood vengeance. A mere twelve hours later, Jenatsch was buried, still in his blood soaked clothing, in the Chur cathedral below the former organ.

Where was Jörg Jenatsch buried?

Since the burial, there have been many renovations and rearrangements of the tomb slabs at the cathedral. So the exact location of his tomb became unknown.

In 1959, a Swiss anthropologist Erik Hug identified his tomb and remains based on clothing and head injuries. The remains were reburied in 1961.

Hug reported his findings in several public lectures. But, he never published a scientific paper of the Jenatsch case. So, upon Hug’s death in 1991, all the documents of his Jenatsch research disappeared.

The exact location of Jenatsch’s skeleton was unknown once again, until Hug’s documents were found in a safe inside the monastery shop in 2012.

Genetic analyses of the remains

This time, the researchers wanted to confirm the identity of the rediscovered remains using genetic analyses. Three living relatives of Jenatsch provided DNA samples for comparison.

These three references were all paternal descendants of Anton Jenatsch (Jörg Jenatsch’s great-grandfather), which meant they should share the same paternally inherited Y-DNA as Jörg Jenatsch.

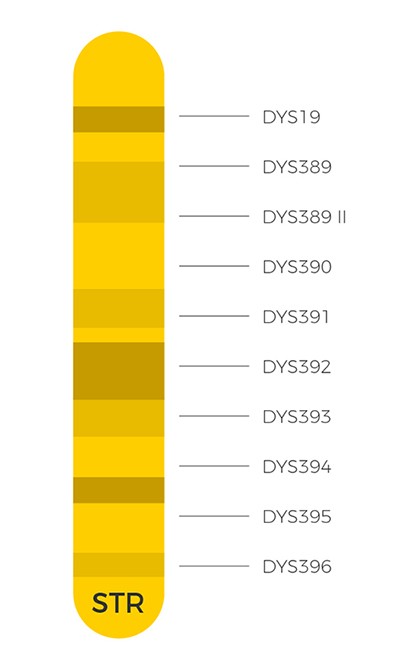

Two types of Y-DNA markers can be analyzed – very slow changing SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) and fast changing STRs (short tandem repeats).

SNP analysis showed that all three references and the presumed skeleton of Jenatsch belong to the same Y-DNA haplogroup (R1b1b2a2g).

Haplogroups are ancient family groups that form the main branches of the Y-DNA evolutionary tree. But, they provide little information for more recent biological relationships. Hence, the researchers then analyzed 23 STR markers from the Y chromosome.

All three living references had an identical Y-DNA STR profile. This profile was similar, but not identical, to the Y-DNA STR profile obtained from Jenatsch’s putative remains.

Given that STR markers are fast-changing, the three differences that existed between the references and Jenatsch’s putative remains are actually entirely possible in the twelve generations separating the three references and Jenatsch.

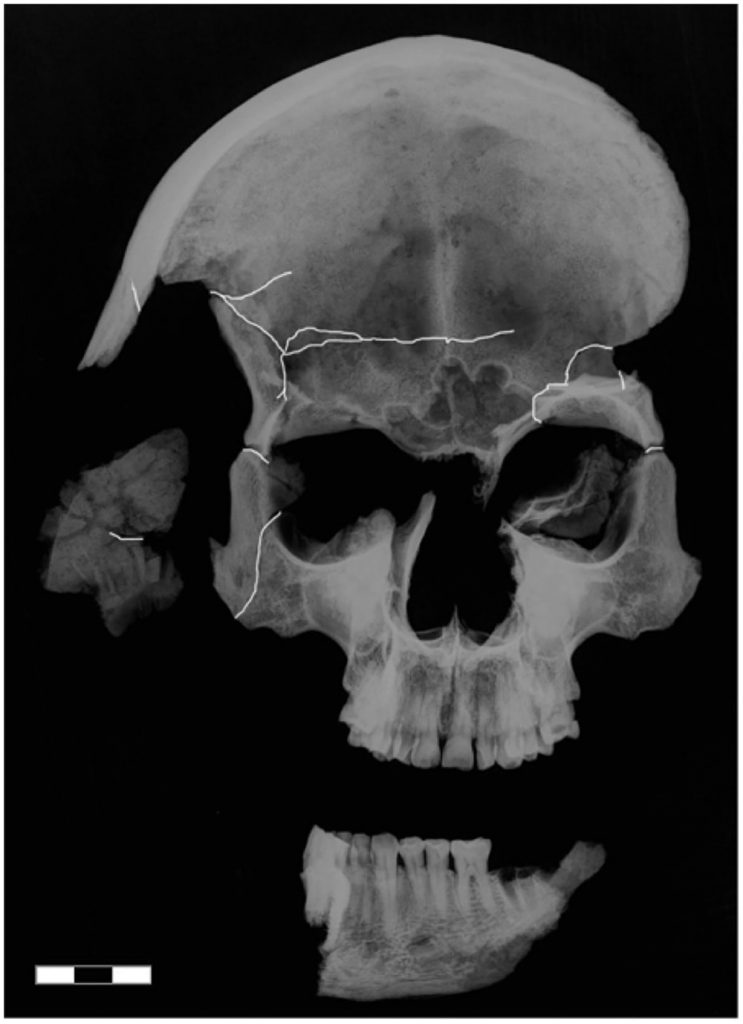

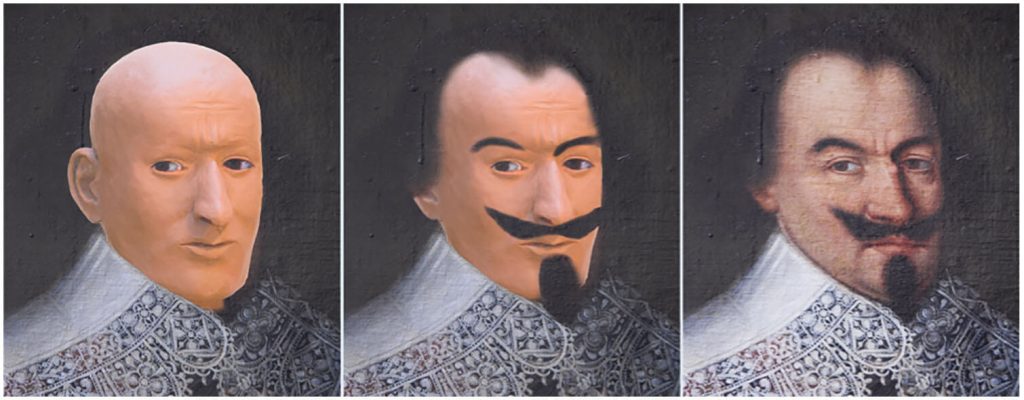

Facial reconstruction from the skull

These genetic analyses provided strong support for the positive identification of Jenatsch’s remains. However, the researchers chose to take the analyses even further.

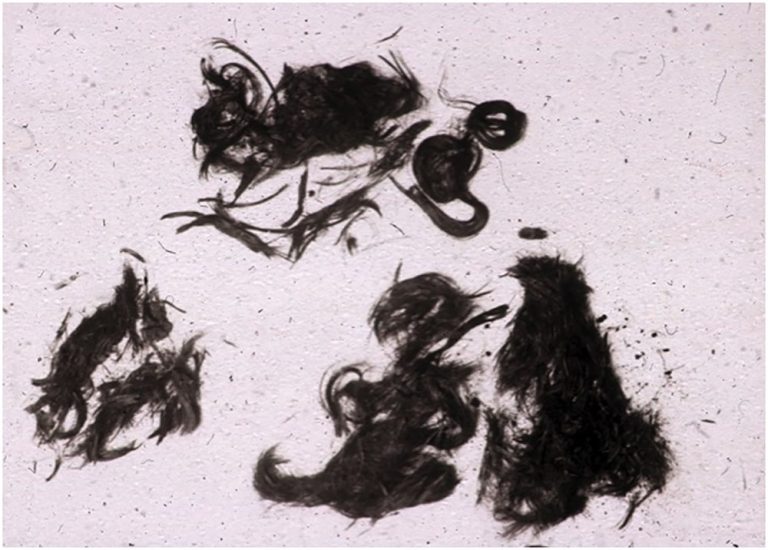

A morphological analysis of the skull showed trauma consistent with the accounts from the night of the murder. Facial reconstruction from the skull matched an oil painting of Jenatsch. Further genetic analyses predicted brown eyes and dark brown hair for Jenatsch, which also matched his portrait.

This comprehensive analysis of the remains is sufficient to dispel any doubt that the skeleton identified in 1959 indeed belongs to Jörg Jenatsch.

Since his death, a novel by Conrad Meyer has immortalized the life of Jenatsch. He was the subject of many plays and biographical studies in the 19th century. They emphasized his fiery character and his deep devotion to his fatherland.

The DNA tests conducted in these studies have also defined the Y-DNA STR profile of Jörg Jenatsch. If you have taken the DNA Paternal Ancestry Test you can now determine if you have descended from the same paternal lineage as this Swiss political leader.