One night, while they were under the imprisonment of the Bolshevik secret police, the entire Romanov family simply vanished. Amid rumors and conflicting information released by the Soviet leadership, the fate of this Russian imperial family remained unknown.

More than 70 years after their disappearance, a mass grave was discovered near where they were held captive. And genetic analyses confirmed what had long been feared – Tsar Nicholas, Tsarina Alexandra and at least three of their children were brutally executed on that fateful night in July 1918.

Who were the Romanovs?

The House of Romanov was the second dynasty to rule Russia. Tsar Nicholas II, the last ruler from this imperial family, was the eldest son of Emperor Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna of Denmark.

He married Princess Alix of Hess and by Rhine, one of Queen Victoria’s granddaughters. Princess Alix was given the name Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna when she was received into the Russian Orthodox Church upon her marriage to the Tsar.

The couple had four daughters (Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia) and one son (Alexei). Alexei suffered from haemophilia B, an inherited blood clotting disorder caused by mutations in the F9 gene. It was known as the ‘royal disease’ at the time, because the mutation was passed down through two of Queen Victoria’s daughters to various royal families across Europe.

The execution of Tsar Nicholas II

At the end of the February Revolution (the first of the two Russian revolutions in 1917), Tsar Nicholas was forced to abdicate. In March 1917, the entire Romanov family and their loyal servants were put under house arrest, before they were evacuated to Tobolsk.

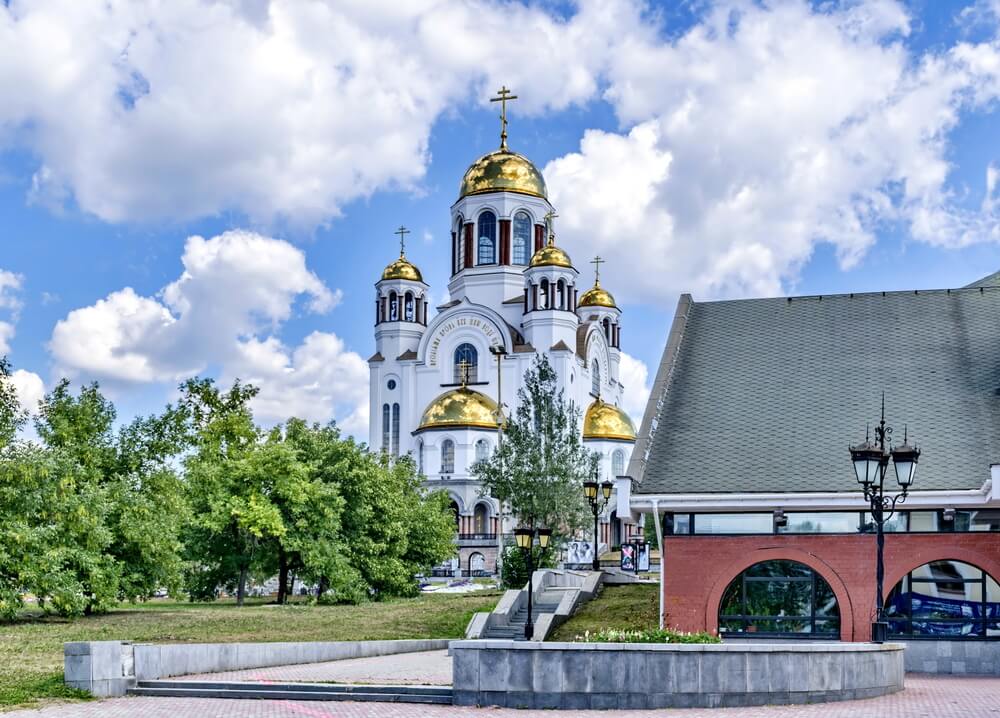

When the Bolsheviks came to power later that year, the Romanov’s imprisonment conditions grew stricter. By May 1918, the Romanov family, plus three servants and the family doctor, had been moved to Ipatiev House at Ekaterinburg, in the Urals of Central Russia.

Then the Bolsheviks announced the execution of Tsar Nicholas in July 1918. According to the official press release “Nicholas Romanov’s wife and son have been sent to a secure place.”

What happened to the rest of the Romanovs?

In the following years, the Soviet leadership continued to release conflicting information regarding the fate of the remaining Romanovs. Some reports stated they were all murdered, while others outright denied that they had killed the other family members.

Finally in 1926, the Bolsheviks acknowledged the murders of the Romanov family. However, they still denied responsibility and claimed that the bodies had been destroyed. Numerous people came forward claiming to be members of the Romanov family in the ensuing years, including Anna Anderson, the most famous Romanov imposter.

Discovery of the remains

The fate of the Romanovs remained a mystery until 1991, when nine human skeletons were discovered in a shallow pit about 20 miles from Ekaterinburg. Historians speculated that the remains belonged to the Romanov family.

DNA testing was performed in an attempt to identify the remains. Three types of DNA tests were used to confirm the identity of the Ekaterinburg remains – gender determination, relationship testing and mitochondrial DNA analysis.

The science behind the genetic analyses

Gender determination:

The gender of each of the nine skeletal remains were confirmed by analyzing a region of the amelogenin gene. This is a robust technique for gender analyses of unknown remains, because the X and Y chromosome have different versions of the amelogenin gene. This allows researchers to distinguish between female remains (with 2 X chromosomes) and male remains (with one X and one Y chromosome).

Relationship testing:

Autosomal STR (short tandem repeat) markers were used to determine whether the nine skeletons were immediate family members. This technique is useful for looking at ancient and degraded DNA samples, because only a small region of DNA is required for analysis.

We inherit one copy of each autosomal chromosome from each parent. This means that for each STR, a child will have one marker that matches one parent, and another marker that will match to the other parent.

Autosomal STR analysis can be used for relationship testing in both males and females in recent samples (e.g. paternity and maternity testing), and during the identification of old skeletons.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis:

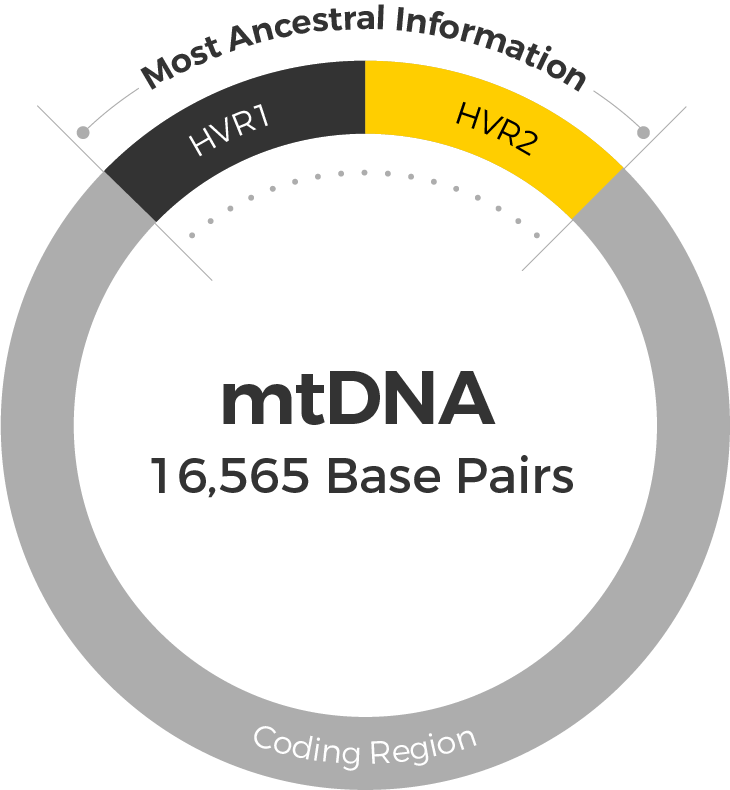

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is different from autosomal DNA, because it’s strictly maternally inherited (passed from mother to child).

Both males and females inherit mtDNA from their mother, so both males and females can take the mtDNA test. However, only females will pass the mtDNA down to the next generation, providing a way of tracing maternal ancestry.

Also, there are hundreds of copies of the mtDNA DNA in each of our cells. This makes it very useful for the analysis of ancient samples.

What did the researchers find out?

The amelogenin gene analyses showed that there were five female and four male skeletons in the grave. Autosomal STR analyses indicated that five of these skeletons were from the same family (two parents and three female children). The other four were unrelated individuals.

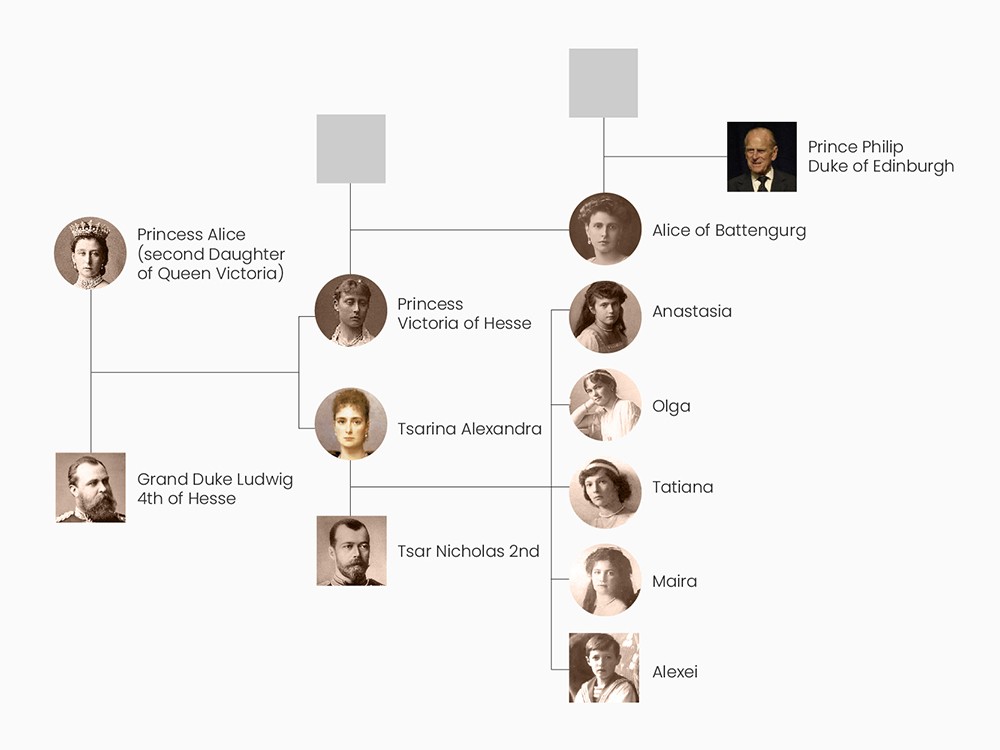

Identifying remains through mtDNA analyses relies on access to DNA from maternal relatives, so the unknown samples can be compared to the reference. Luckily, the family trees of the European royal families are well documented. So it was a simple task to find maternal relatives of the Romanovs.

Identifying Tsarina Alexandra’s remains

Tsarina Alexandra was the maternal granddaughter of Queen Victoria. This means she has the same mtDNA profile as Queen Victoria. Prince Philip is a great-great-grandchild (on the maternal side) of Queen Victoria. Therefore, he also carries the same mtDNA as Queen Victoria and Tsarina Alexandra.

The mtDNA profiles generated from the putative skeletons of Tsarina Alexandra and her three children, matched to the mtDNA profile of Prince Philip.

- This provided very strong evidence that the skeletal remains were maternal relatives of Prince Philip, and likely the remains of the missing Romanov family.

The remains of the Tsar

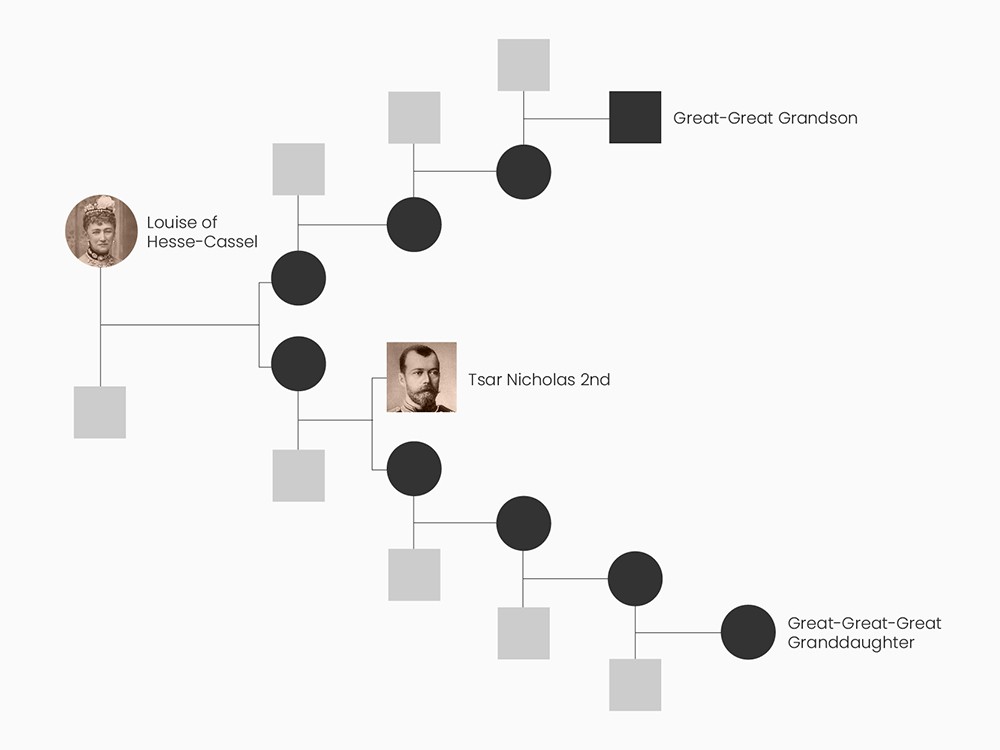

To confirm the identity of Tsar Nicholas, mtDNA profile from his putative skeleton was compared to mtDNA profiles obtained from two living maternal relatives.

The mtDNA profile from the putative skeleton of Tsar Nicolas matched the mtDNA profile of the two living maternal relatives, except at position 16169. It first appeared that Tsar Nicholas had a C nucleotide at position 16169, differing from the T nucleotide found in the reference samples.

However, closer examination revealed that Tsar Nicholas actually had a mixed mtDNA profile. This is known as heteroplasmy, where some of his mtDNA was 16169 C, while some was 16169T.

Heteroplasmy is very rare. So it immediately raised questions about the authenticity of the genetic analyses. Some groups claimed it was due to contamination with modern DNA samples.

A later study from the skeletal remains of Georgij Romanov (Tsar’s Nicholas’ brother) determined that Georgij’s mtDNA profile was a perfect match to the Tsar’s profile. It even included the same heteroplasmy at position 16169.

- These studies provided very strong evidence that researchers had accurately identified the remains of Tsar Nicholas.

Conclusions

The mtDNA profiles of members of the Romanov family have now been defined. Both the Tsar’s and Tsarina’s lineages include many notable historical figures who would share the same maternal mtDNA markers as members of the Romanov family.

If you have taken the DNA Maternal Ancestry Test, you can compare your mtDNA against members of this notable family to see if you may have also descended from royalty.

The skeletons of the Tsar, Tsarina, and three of their daughters were reburied with honours in the imperial-era capital of St. Petersburg. But what happened to the remaining daughter and their son, Alexei?

Had two Romanov children really escaped from the execution? Or were all the family members killed, as per the memoirs of Yurovsky, the Bolshevik officer in charge of the Romanov’s captivity? Continue reading here to follow the remainder of this fascinating story.

References:

Stone R. (2004) Buried, Recovered, Lost Again? The Romanovs May Never Rest. Science. 303(5659):753.