To the Georgian people, Queen Ketevan is a martyr and a saint. She opposed aggression, dedicated her life to religion and charity, and chose death over renouncing Christianity. This is the story of the hunt for the relics of Queen Ketevan. And how DNA analyses established a relic found in Goa, India belongs to this Saint of Georgia.

Queen Ketevan

Queen Ketevan was a Christian queen of Kakheti, a kingdom in eastern Georgia. Her reign as the queen lasted just a single year, coming to an abrupt end with the sudden death of her husband (King David I) in 1602. King David’s ill father returned to the throne, until he was murdered by Constantine (another of his sons).

Ketevan enlisted and led the Kekhetian nobles against this patricide, leading to the death of Constantine in battle. Despite the trauma and deaths caused by the enemy soldiers, Ketevan ordered they should receive medical treatment and were accepted into service if they desired. She even had Constantine’s body respectfully laid to rest.

The capture of Queen Ketevan

After the death of Constantine, Ketevan’s young son, Teimuraz, became the king of Kakheti, with Ketevan acting as a regent. For several years, Teimuraz reigned in peace, until the threat of attack from nearby Iranian armies.

In 1613, Ketevan travelled to Iran to negotiate with Shah Abbas of Iran, and surrendered herself as an honorary hostage in a bid to protect her kingdom. Sadly, her surrender failed and a long-lasting battle began between Teimuraz and the Iranian armies.

For ten years, Ketevan was held captive in Iran, and she was tortured to death with hot pincers for refusing to renounce Christianity and convert to the Islamic faith.

Loss of Queen Ketevan’s remains

Ketevan’s charity, religious strengths and her wish to sacrifice herself to try to save her kingdom earned her great respect, and in the final year of her imprisonment, two friars had become close to Ketevan, earning her trust and confidence.

After her death, they secretly unearthed her remains and kept them hidden for three years, before returning them to her son, Teimuraz. The Alaverdi cathedral holds most of Ketevan’s remains, except for her right arm bone which is kept at St Augustine convent in Goa, India.

According to records, the remains from Alaverdi were later lost, when the horse transporting them to a safer location slipped and fell in a river.

Her arm bone becomes a religious relic

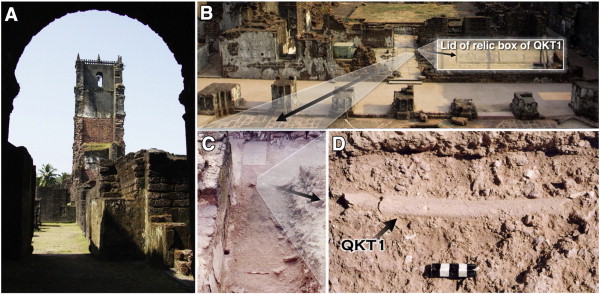

The Georgian Orthodox Church canonized Ketevan shortly after her death. This meant her arm bone in Goa was now a religious relic. It was protected and honored, as the St Augustine convent was enlarged and rebuilt through the 15th and 16th centuries.

But by 1842, the convent had collapsed, and Ketevan’s arm bone was lost in the ruins. Since 1989, many different groups have attempted to find this religious relic.

Finally after 15 years of searching, an arm bone was discovered and the intact lid of the stone relic box was found nearby. Two other bone fragments were also discovered during the search. Historical records indicate they belong to the two Indian friars.

Genetic analyses of the remains

Researchers turned to DNA analyses to confirm that they had really discovered the long-lost remains of Saint Ketevan.

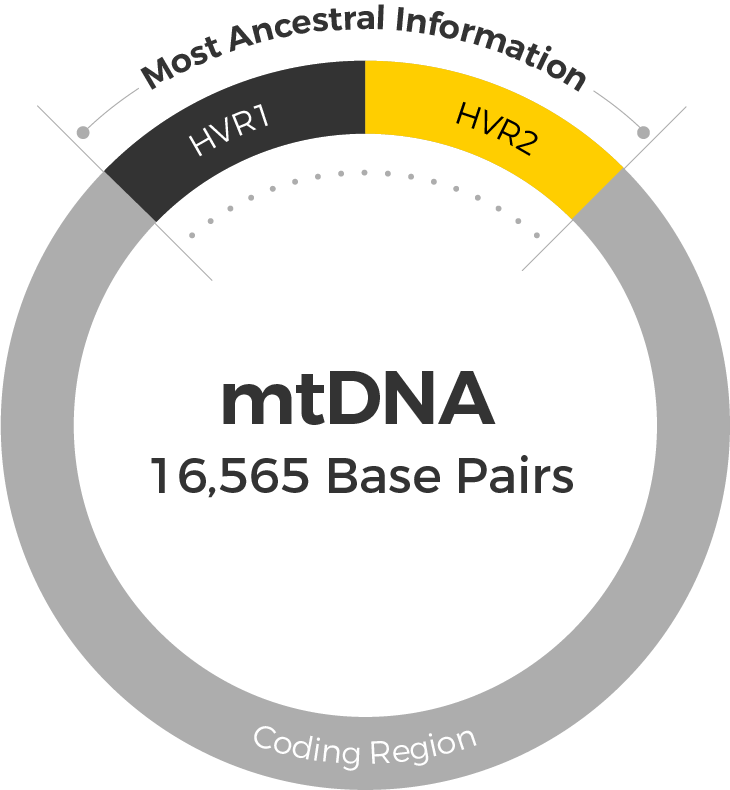

They elected to analyze mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as a way to trace the geographical origin of the arm bone and the other two bone fragments.

There are hundreds to thousands of copies of the mtDNA genome in nearly all of our cells, increasing the likelihood of obtaining suitable DNA from ancient remains.

The strict maternal (mother to child) inheritance of mtDNA ensures that it remains essentially unchanged for many generations. Therefore, it’s useful for tracing maternal lineages, back hundreds of years.

The analysis of mtDNA also allows the determination of mitochondrial haplogroups, which are the major branches (or family groups) of the mitochondrial evolutionary tree – the phylogenetic tree that shows how maternal lineages are all connected together.

As expected, the two bone fragments suspected to belong to the two friars generated mtDNA profiles (haplogroups R6a and U2a) typical of Indian populations.

The DNA profile from the presumed arm bone of Saint Ketevan belonged to haplogroup U1b. This haplogroup is found at moderate to high frequency in Georgia. It was absent from all of the reference samples taken from people in India.

Genetic analysis of the gender-specific amelogenin marker confirmed the gender of this arm bone to be female. These DNA analyses support the archaeological findings and historical records, which means the long-lost relic of Saint Ketevan has been found.

Authenticity confirmed

With its identity confirmed, the much-anticipated relic can now be honored and respected by all those that value the heroic Saint Ketevan. These genetic analyses have also defined the mtDNA profile of Saint Ketevan and two Indian friars.

If you have taken the DNA Maternal Ancestry Test, you can compare your mtDNA against these profiles to see if you may have descended from one of the same maternal lineages.