Scythians were an ancient nomadic people whose origin and disappearance remains a mystery to this day. Scientists have been piecing together their history by studying DNA from remains found in ancient burial sites. Between 1996 to 1997 two skeletons were discovered in a Scytho-Siberian kurgan from 2500 years ago, genetically linking Scytho-Siberians and the Chinese kingdom.

Who were the Scythians?

The Scythians were a branch of ancient nomadic people who prospered for most of the last seven centuries BC. They resided in a region of Central Eurasia that stretched from the countries surrounding the Black Sea across Kazakhstan and lower Russia, and south into Afghanistan and Iran.

Despite the rich history, the origin of Scythians and why they disappeared is unknown. It’s widely believed that the Scythian civilization first developed in the second millennium BC. This corresponds to the time of pastoral nomadism (when people migrated to find pasturage for their domesticated livestock), and the production of bronze and iron.

Excavating Scythian kurgans

Much of our current knowledge of Scythians come from excavating their burial places, known as kurgans. A kurgan is an ancient burial mound, heaped over a burial chamber.

Elite members of Scythia were buried in kurgans with sacrificial offerings that include weapons, horses and chariots.

Based on the skulls and facial features of the excavated remains (craniofacial data), the Scythians are believed to be of mixed Euro-Mongoloid origin (also known as Eurasians) with both European and Asian features.

No living descendants

We often think of Siberia as a barren land that is inhospitable for inhabitance. However, there’s evidence that Scytho-Siberians inhabited south Siberia, the eastern most part of Scythia. Some Scytho-Siberian cultural traits are still present in several modern populations, but identifying living descendants of this population is difficult.

Also, there isn’t much biological data to characterize Scytho-Siberian people. Mass population movements that happened in southern Siberia and Central Asia during the last 2,500 years further complicate this task. They include the movement of the Huns, the formation of the Turkic kaganate, and the influences of Genghis Khan.

Genetic analyses of remains from ancient burial places

So far, analyzing the DNA of Scytho-Siberian human remains found in kurgans and from tombs of the Scytho-Siberian culture has proven one of the best ways to trace the ethnic origins of the Scythians, and their relationships to other European and Asian populations. So, scientists were very excited when 300 archeological monuments were discovered in the valley of the Sebystei River in 1996 and 1997.

Amongst these discoveries were a number of Scytho-Siberian kurgans dating back 2,500 years. In two of these kurgan, they found bone-arrowheads and ceramic vases typical of the Pazyruk culture, together with sacrificial gifts that were typical of the Scytho-Siberian culture.

The human remains from the first kurgan (referred to as SEB 96 K1) belonged to a man 24 to 30 years old. The second kurgan had a boy (referred to as SEB 96 K2), 2 to 3 years old at the time of death.

The science behind DNA analyses

DNA analyses is useful for identifying the relationship between the individuals (the kurgans were in close proximity to each other), and for tracing their maternal ancestry.

Relationship testing uses autosomal STRs (short tandem repeats). A person has two sets of autosomal STR markers inherited from each parent. So if the remains belong to a father and a child, half of their STR markers would match.

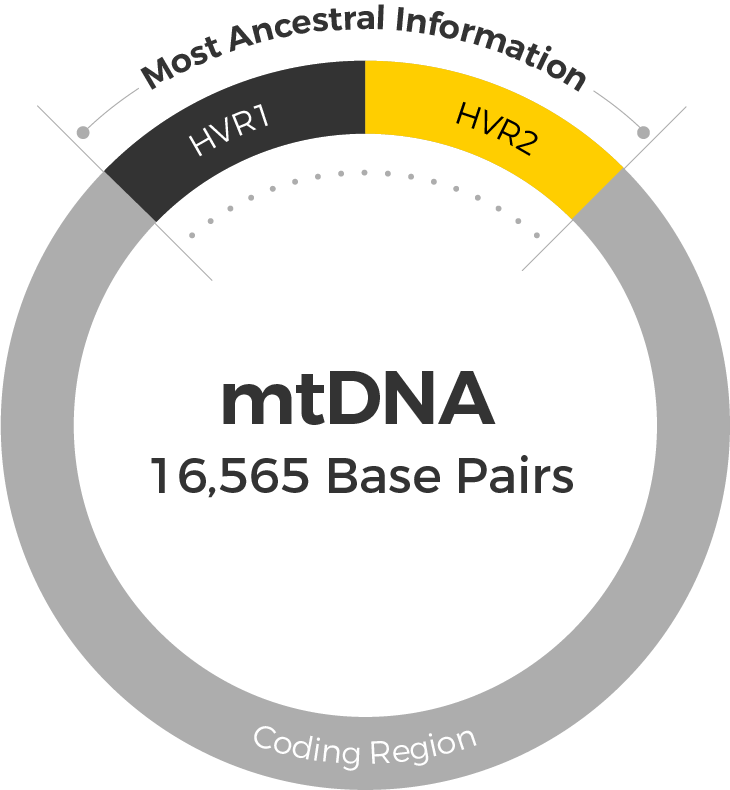

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is very useful for analyzing ancient samples. They have a high copy number, a rapid evolution rate, and are strict maternal (mother to child) inheritance.

MtDNA profiles allow researchers to place ancient remains on the mitochondrial evolutionary tree. An evolutionary tree is similar to a family tree, and maps how different populations in the world are related. Haplogroups identified by letters are the major branches of this evolutionary tree.

What did they find?

Autosomal STR profiles showed that while the kurgans were located in close proximity, the two individuals were not related.

The adult male (SEB 96 K1) belonged to mitochondrial haplogroup F2a. The young boy (SEB 96 K2) was a member of haplogroup D. These distinct mtDNA profiles further confirmed the absence of a close parentage relationship between the two skeletons.

The haplogroup F2a (of the adult male) is common in east and central Asian populations. However, does not appear in Siberian or North American populations. On the other hand, haplogroup D (of the boy) is common in Chukotkan (Eskimo Siberian, and Chukchi) and Kamtchatkan populations.

These DNA findings suggest a genetic link between Scythians and populations living in China. More specifically between the Altaic Scytho-Siberian populations and populations from Chinese kingdoms at the time.

The DNA tests conducted in this study have defined the maternal lineage profiles of two members from an ancient Scytho-Siberian population. If you have taken the DNA Maternal Ancestry Test, you can compare your DNA and find out whether your mtDNA matches the maternal lineage of either of these two ancient Scytho-Siberians.