Long ago, the Irish Celts worried about “fairies” replacing their children with changelings or fairy children who suffered from unexplained diseases. The most common disease was “having too much iron in the blood,” apparently diagnosed when a child cringed away from an iron bar.

The story might be folklore, but the disease is real. Hereditary hemochromatosis is quite prevalent among people who are of Northern European or Viking descent.

What is hemochromatosis?

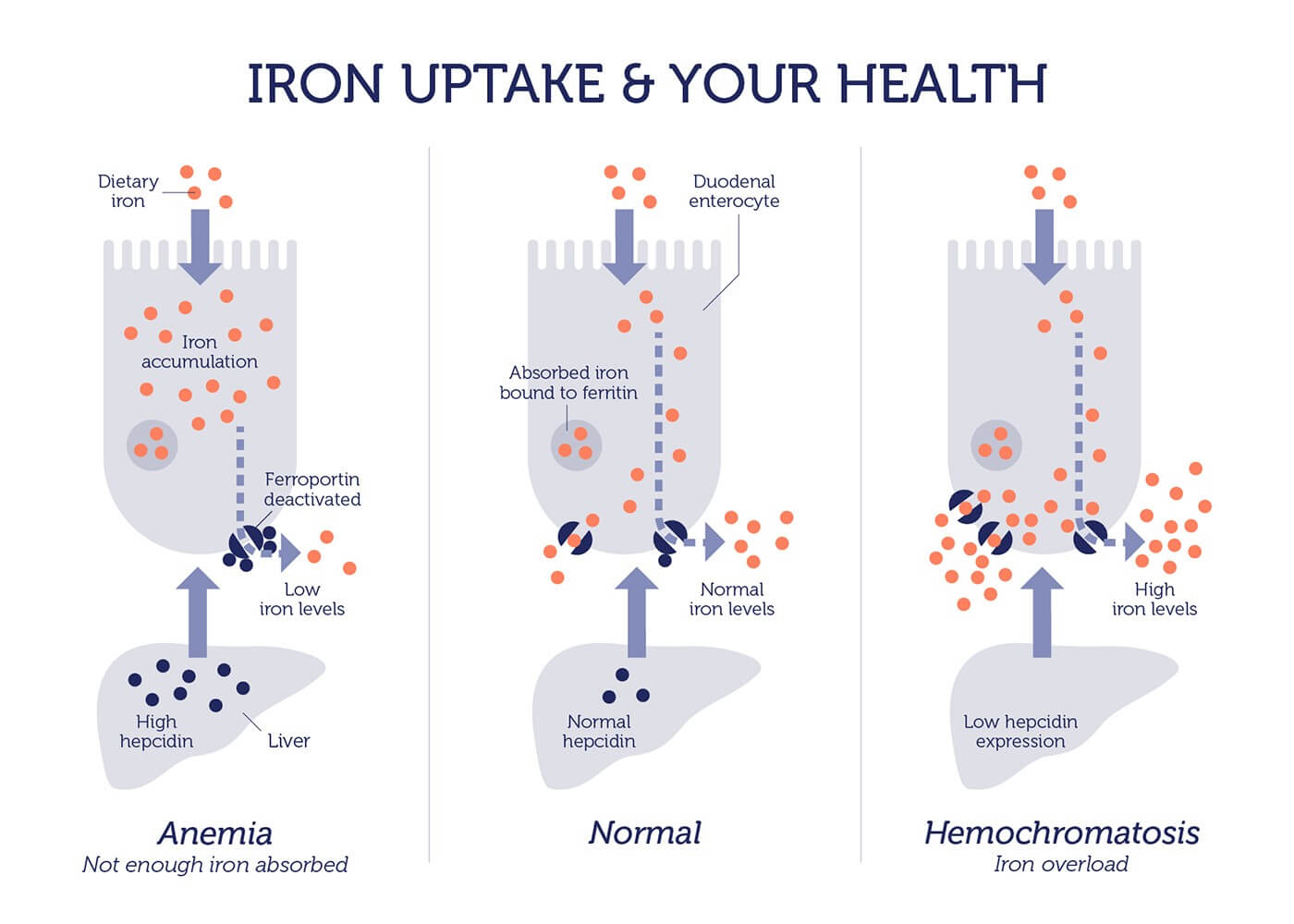

Hemochromatosis is a condition where the body absorbs and stores too much iron. It is one of the most common genetic disorders in the US.

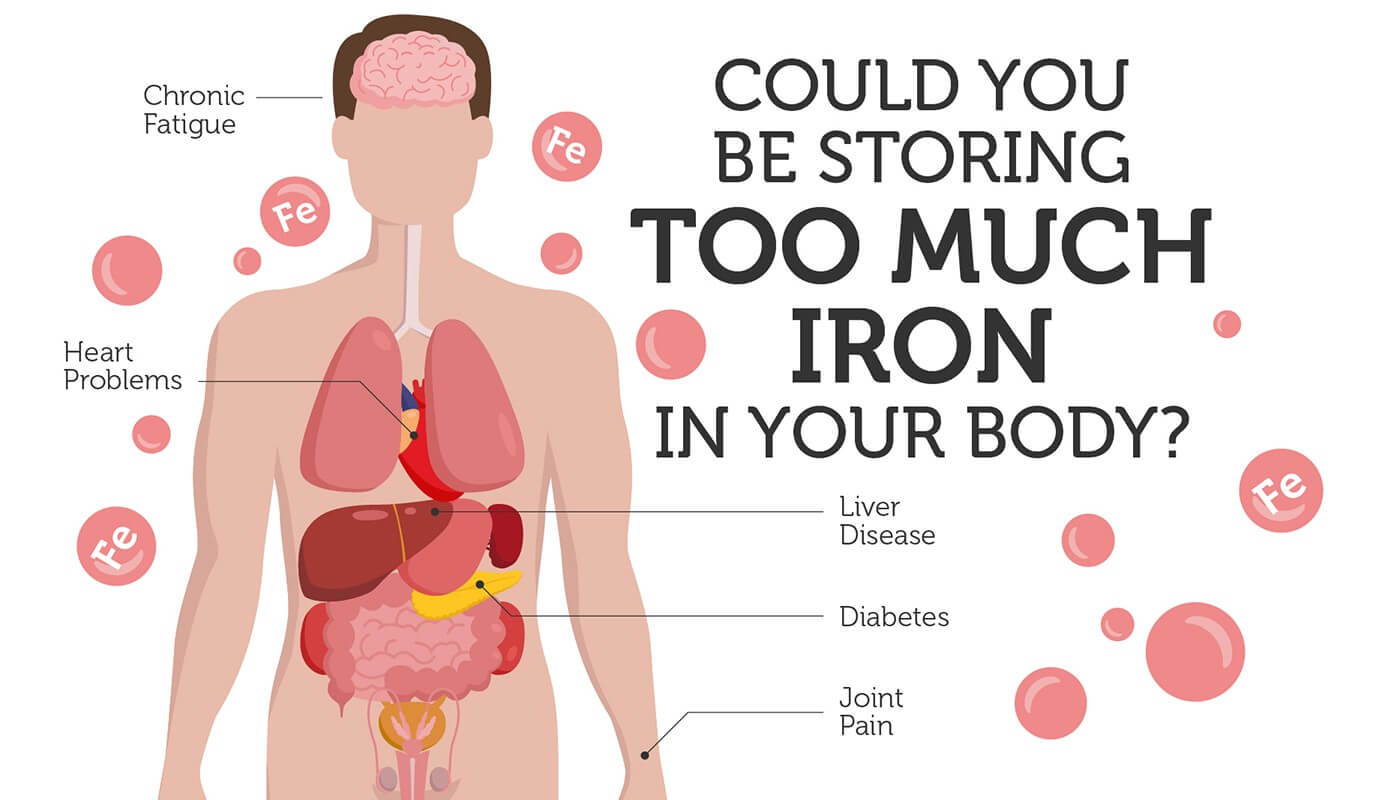

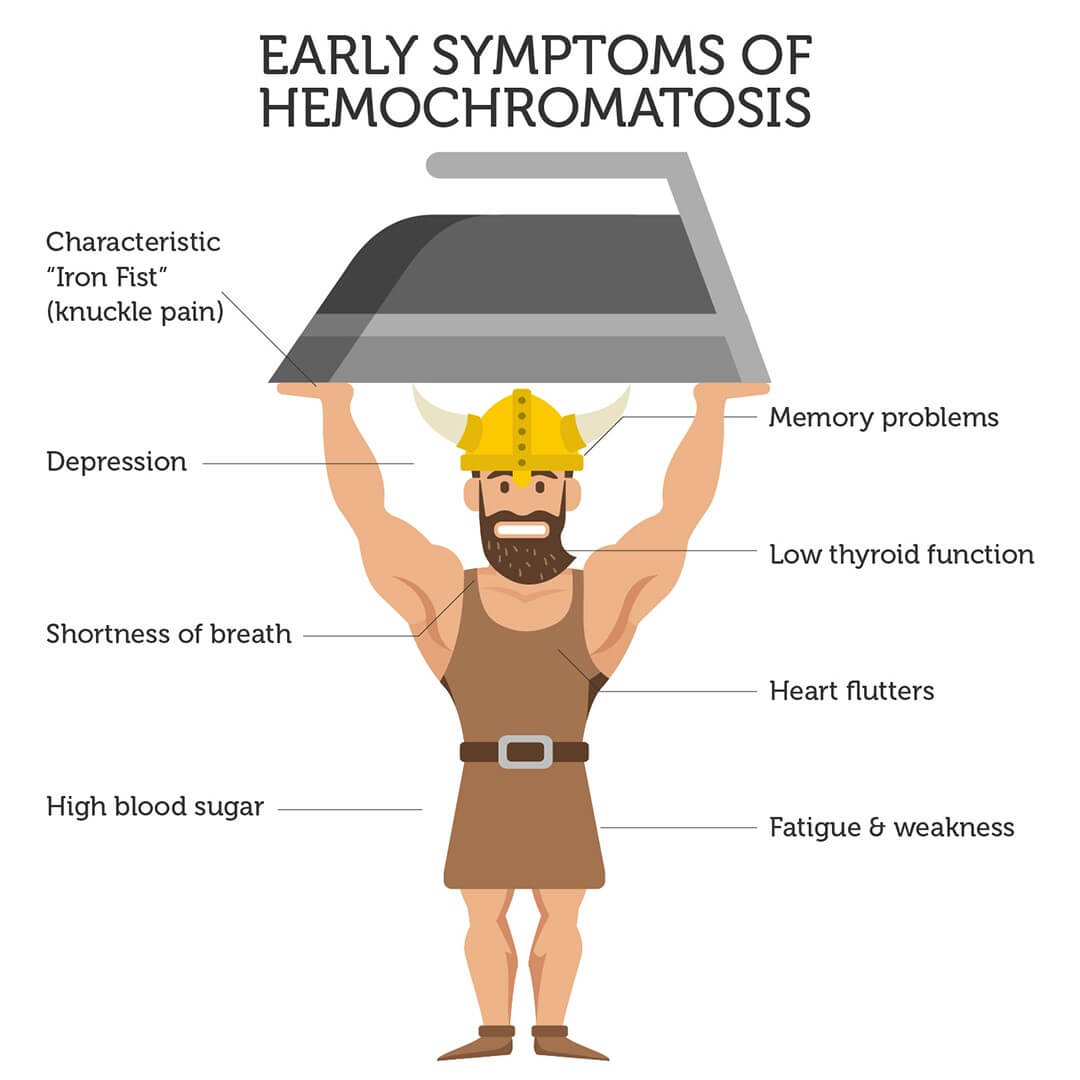

Chronic fatigue, joint pain and heart problems are among the initial symptoms of hemochromatosis. Advanced symptoms include arthritis, diabetes, heart disease and liver failure.

Unfortunately, these symptoms resemble many other conditions. As such, hemochromatosis is often not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, because the underlying cause (excess iron) is often missed.

The HFE gene

The leading causes of hereditary hemochromatosis are defective versions of the HFE gene. This gene encodes the HFE protein, which controls the amount of iron absorbed from our food.

People with defective HFE absorb three times more iron than normal. Since humans are unable to dispose of any extra iron, it accumulates in organs, causing organ damage or literally “rust” over time.

A founder mutation

One of the hemochromatosis-causing HFE changes likely occurred in a common ancestor, or a ‘founder’, shared by Northern Europeans of Viking descent. The affected person then passed on the DNA change to their descendants.

This “founder affect” explains why 80-90% of people with hemochromatosis carry the exact same HFE genetic mutation. On the plus side, these genetic changes are useful for easily diagnosing the risk of hemochromatosis.

This is good news to the 33 million Americans, who are either silent carriers (have one defective copy), or have two defective HFE genes, and are at a high risk of developing hemochromatosis.

In the spotlight

Hemochromatosis received much-needed awareness in 2009 when a researcher studying the “Black Plague” bacteria mysteriously died.

Malcolm Casadaban was working with a variant strain of the Yersinia pestis bacteria, which had been engineered so it required iron to survive. But, Casadaban had undiagnosed hemochromatosis and his high iron levels made him vulnerable to even this weakened form of Yersinia pestis.

Are you at risk?

Hemochromatosis is a silent killer, because it is regularly undiagnosed or diagnosed after the extensive organ damage has already occurred. If diagnosed early, it can be easily treated and managed through phlebotomies (removing blood at regular intervals) and dietary changes.

Does your Viking ancestry put you at risk of “the Celtic Curse?” Find out if you are at risk with the DNA Hemochromatosis Test.