Remember that Friends episode where Chandler fell asleep at a meeting, and ended up with a job in Tulsa? How about the time the bus driver had to wake you up at the end of the line? Or that high school teacher who always fell asleep during detention?

It happens to the best of us – when meetings are called for in the afternoon, and when the caffeine is not in abundance. We are quick to blame big meals, not enough sleep, or lack of exercise for our afternoon slump.

But, what about our genes? Narcolepsy is one such extreme sleep disorder, influenced by DNA changes in the HLA-DQB1 gene.

The science behind sleep

Sleep is one aspect of our biology that remains a bit of a mystery even to scientists.

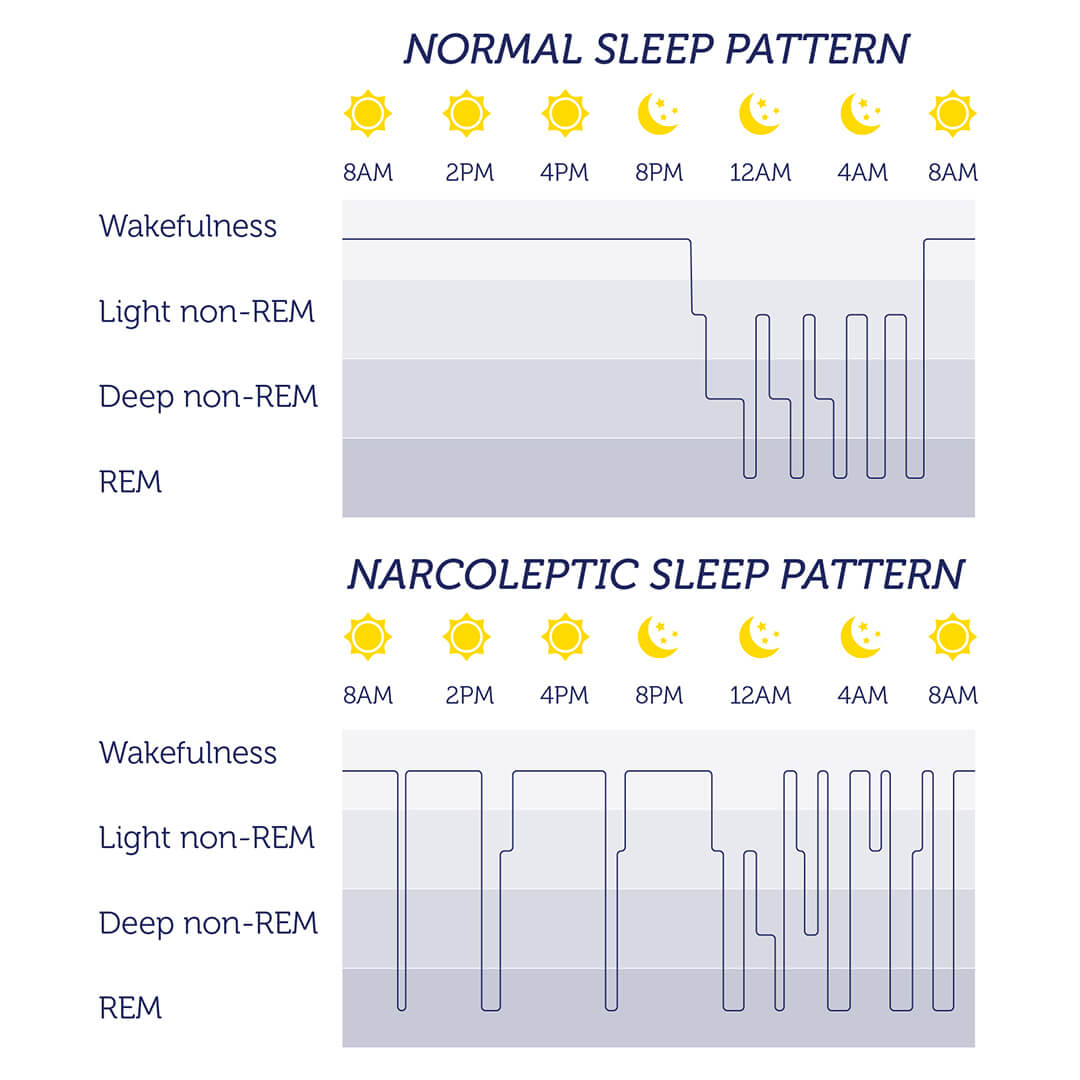

Depending on how long we sleep, we go through four to six separate sleep cycles. Each cycle lasts about 100-110 minutes. There are two distinct phases to each cycle: (1) non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and (2) rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

We enter REM sleep about 70-90 minutes after falling asleep. During REM sleep, our brains becomes active. This is when we dream, and experience temporary muscle paralysis. If you have ever woken up in the middle of a bad dream, you may have experienced a very brief moment of sleep paralysis.

What is narcolepsy?

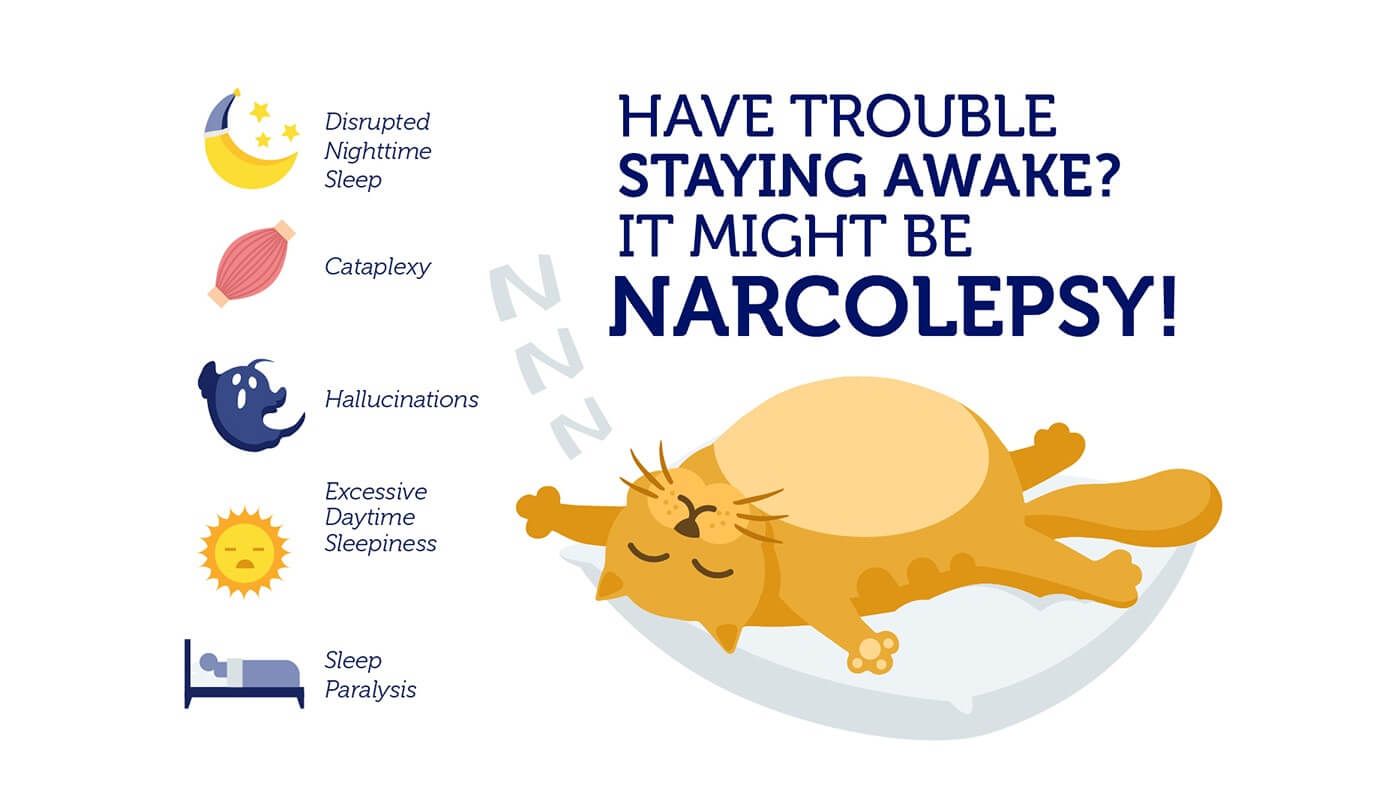

People with narcolepsy enter REM sleep just a few minutes after falling asleep. This explains the symptoms associated with narcolepsy – sleep paralysis, vivid hallucinations and collapsing into a sleep-like state while remaining conscious (called cataplexy).

Cataplexy

Cataplexy can be terrifying, because even though people with narcolepsy are conscious, they are unable to move or speak due to paralysis. Just an emotion can trigger cataplexy, which is extremely dangerous in some situations, like driving or crossing the street.

Even with many involuntary naps during the day, narcoleptics are constantly sleep-deprived, because their night sleep is interrupted by frequent awakenings.

Adding insult to injury, a long list of health risks, including high blood pressure, obesity and decreased resistance to viral infections, are also associated with sleep-deprivation.

Diagnosing narcolepsy

One way to diagnose narcolepsy is by looking at the levels of the neurotransmitter hypocretin (also called orexin). Hypocretin is a chemical produced in the brain that controls alertness and prevents REM sleep.

People with cataplexy have lower levels of hypocretin, because the nerve cells (neurons) that produce hypocretin have died off. Over 90% of these patients also have DNA changes in the HLA-DQB1 gene, which is thought to play a role in regulating hypocretin levels.

The HLA-DQB1 gene

The HLA-DQB1 gene normally encodes a protein that is involved in signalling the immune system against foreign bodies (e.g. bacteria and viruses). People with the HLA-DQB1 variant are genetically predisposed to narcolepsy.

They make a protein that recognizes the hypocretin-producing cells as foreign, and signals for them to be killed. This increases the risk of narcolepsy by 7- to 25-fold, compared to someone with the normal version of the gene.

Getting enough sleep

There is no cure for narcolepsy, but the symptoms can be managed through medications that improve the level of alertness.

A large proportion of us don’t get the recommended eight hours of sleep a night and are most likely sleep-deprived. However, to experience what a non-medicated narcoleptic feels like every day, you would have to stay awake for two to three days straight!

Are you at risk?

More than 250,000 Americans suffer from narcolepsy. Only 25% of these cases are accurately diagnosed, because narcolepsy is often mistaken for depression, epilepsy or bipolar disorder, or simply dismissed as laziness. If you suspect you may have narcolepsy the DNA Narcolepsy Test can help you accurately diagnose your condition.